Cyclotron

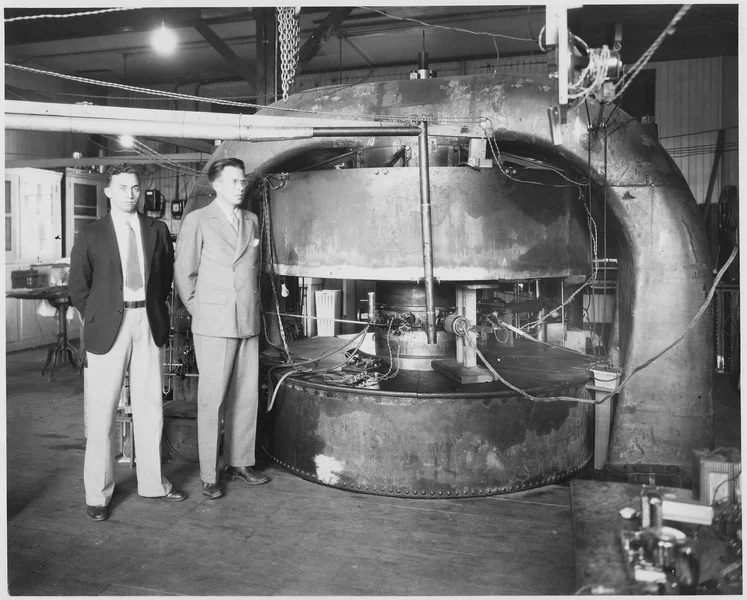

M.Stanley Livingston & Ernest O. Lawrence in front of the 27-inch cyclotron at the old Radiation Laboratory NARA 558593.tif.jpg

the tron machines of the Cold War are legendary. It all began with the cyclotron. The historians John Heilbron and Robert Seidel discovered that the origin of “cyclotron” was really at first “a sort of laboratory slang” as early as 1933. Built by Ernest O. Lawrence at the University of California, Berkeley, the cyclotron was a creation of the 1930s. Formally, Lawrence insisted that his device be called a “magnetic resonance accelerator” but that unwieldy title was officially changed in 1936 to cyclotron. As Heilbron and Seidel point out, the term cyclotron “echoed” Rolf Wideröe’s earlier description of an accelerator tube only now in a circle but was also “an analogy to ‘radiotron,’ ‘thyratron,’ and ‘kenotron’.”[1] Importantly, Lawrence and his cyclotron became a new household word in 1937 when Time magazine painted a picture of the world of science moving from old England epitomized by Ernest Rutherford to new America exemplified by Ernest Lawrence.[2] Nearly a decade later, the public read in James Phinney Baxter’s gripping account of the technological breakthroughs during World War Two how Lawrence had solved the problem of isotope separation by re-making his 184-inch cyclotron into the “Calutron” to obtain one microgram per hour of U-235.[3] The cyclotron begat a tron lineage which grew to dominate nuclear physics. As cyclotrons proliferated, newer and larger accelerators like the synchotron and then the Cosmotron (with its 24 ignitron rectifiers[4]), Bevatron, and Tevatron offered Cold War era physicists the possibility of creating new elements and peering further inside the atom. Later still came the torsatron and the Vintrotron, which themselves grew from Lyman Spitzer’s stellarator design for controlled nuclear fusion.[5]

[1]. John Heilbron, and Robert Seidel. Lawrence and His Laboratory: A History of the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. (University of California Press, 1989), 84.

[2]. Michael Hiltzik, Big Science: Ernest Lawrence and the Invention that Launched the Military-Industrial Complex (Simon & Schuster, 2015), 168.

[3]. James Phinney Baxter, Scientists Against Time (Little, Brown and Co., 1946), 429.

[4]. ‘The Cosmotron – It Works,’ Nucleonics (July 1952): 34-35.

[5] S. Nagao and Y. Abe, “The Vintotron – a Helical Axis Torsatron,” Nuclear Fusion 26 (1986): 671.